Sometimes, growth is predictable and measured— the slow unfurl of a seed, the waxing of the moon through full, the steady lengthening of hair. Sometimes growth goes less expected— the emergence of new shoots from a dead tree, the partnering of fungi and algae to become lichen, the rapid divisions of mutated cells.

I’ve let this newsletter fall away more than I would have liked over the summer and I’m in the midst of rethinking and reworking my approach to it a bit (you may notice I am not currently adhering to my intended full moon edition schedule). The reason for all this is simply that I’ve been distracted. This spring I was told I have breast cancer and I’ve been moving through the diagnostic and beginning treatment phases of that. It’s treatable. It’s being treated. But it’s been quite a lot to adjust to.

Cancer is a disease of uncontrolled growth. It’s driven by cells that act abnormally, that won’t follow the usual signals or pathways. Parts of the body gone rogue. The body destroying itself from within.

It’s hard not to draw comparisons between cancer and environmental destruction, to connect the disease to the ways in which we poison our world and so poison ourselves. It’s hard not to draw the comparison between cancer and capitalism, the unchecked growth, the insatiable hunger to expand even when that expansion destroys the whole. So here I am drawing those comparisons.

They don’t know why I have cancer, why I have it now, at a relatively young age, or why I have the kind of cancer I have, one that does not seem to run in my family. The kind of cancer I have is on the rise among young people. They don’t know why that is.

My initial reaction to my diagnosis was a strong desire to retreat to some isolated woods somewhere until I was well again. So I wouldn’t have to put anyone else through this. I imagined myself building a house of fallen branches and moss, keeping company with only the trees, emerging from the forest only when I was free of cancer with all its complex mutations and, once again, simply myself.

Of course, the actual experience is far different from my little hermit fantasy. As I’ve embarked on cancer treatment, I’ve felt an intense sense of interconnectedness. Friends and family and loved ones— both human and not— offering care and support in some very deep and foundational ways. In a forest ecosystem, trees will do this—help each other, direct resources to the sick, keep alive what would die without community. Sometimes I think our human root systems expand farther than we know, deeper than we realize, are even more interconnected than we can ever fully perceive.

Finding the Poetry

I’m reading a lot about cancer. Mostly poetry. I love the way poetry can get at things slantwise, turn them over and over in many different angles of light, and reveal the magic there. I love the way poetry can find the strangeness in the mundane, the small incremental moments that make up the expansive, the non-linear non-narrative non-logical not-quite-here-or-there of it all.

In the cancer poetry I find myself most drawn to there’s a sense of connection between illness and nature, the transformations contained in the brushing up against death, an uncanny merging between human and nonhuman. It’s the poetry that embraces that liminal space and the possibility of rooting into uncertainty. Take Katie Farris’s “What Would Root,” for example:

Everything was everything: the twigs in my eyes

tasted sunlight with my mouth, the roots drew the salt

from my sweat into their vacuum, and I was no longer hungry.

Everything; it was all green; the roots in my skull shifted and I

lay down beneath my own branches. I had to wiggle a bit to

find a place to lay my head: the rock was very hard

and needed softer ground—yes, a place for the top

of my head to come off, to nuzzle into the earth, to drink.

Farris’s book, Standing in the Forest of Being Alive, draws inspiration from the author’s experience of breast cancer. It’s a deeply embodied book, embracing the erotics of illness alongside the disturbing and distressing natures of cancer and its treatments. What I love about Katie Farris ending her book with this poem and these lines in particular, is that it is far from the poem that we expect from the cancer narratives many people seem to want: narratives of overcoming, of battling it out and winning, or, at the very least, of perseverance in the face of crisis. Instead, this poem embraces the deep strangeness of illness, the way that cancer isn’t actually something you can overcome with any kind of certainty. Maybe they’ll get it all in surgery. Maybe you’ll be in remission. Maybe you won’t have to face it again. But, always, there is that possibility. One stray cell roaming the body, finding another place to dig into. And how do you hold that? What does that make of you? What strange creature?

Katie Farris embraces the uncanny quality to the embodied experience of cancer and cancer treatment, of illness in general, and finds space for it to grow unexpectedly in her poetry, particularly in this poem of transformation and wildness.

Illness can be a kind of liminal space. A move from one state to another. And, as with any in-between space, there’s uncertainty there. Things fall away, are revealed, are clarified. We move through the space and are altered. We emerge into another self, another world, another way of being in the world, another way, perhaps, of writing it.

A Spell for Writing Into It

What is one thing that you feel drawn to write but have kept yourself from writing because it scares you or you aren’t sure how to write it or you simply haven’t felt ready yet? What writing do you feel unprepared for? What writing do you worry might alter you in some unexpected way if you put it on the page?

Perhaps it’s a form. Maybe, like me, you’ve become most comfortable in prose but feel less confident in poetry (over the past few months I’ve been unexpectedly poeming a whole overgrown tangle of verse). Or, perhaps, it’s a subject. Maybe there’s something you want to write about but worry you can’t or shouldn’t? Or it could be a type of experience. Many of us struggle to articulate deeply embodied experiences—sex, illness, birth, death—in words.

Choose one thing that scares you or worries you or that you simply don’t feel full confidence in, and try putting it on the page. Try more than once. Go back to it each day for a week or more. Spend fifteen minutes or an hour or however long you have and feel you need. Just start writing it and see what grows. You don’t have to know what it will grow into yet.

Roots

If you want to read more about the science of cancer and young people, Emily Oster recently wrote about this new study in her ParentData newsletter.

If you want to read more about forest ecosystems, Robert MacFarlane’s “The Secrets of the Wood Wide Web” is a great place to start and Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree is a wonderful deep dive.

If you need more cancer poems in your life, some of my recent favorites are Katie Farris’s Standing in the Forest of Being Alive and Jo Shapcott’s Of Mutability. And some of my beloved essential classics of the genre are Lucille Clifton’s The Terrible Stories and Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals (this one’s not poetry, but prose by a poet). Please send me any and all recommendations (especially the queer ones!)

Happenings

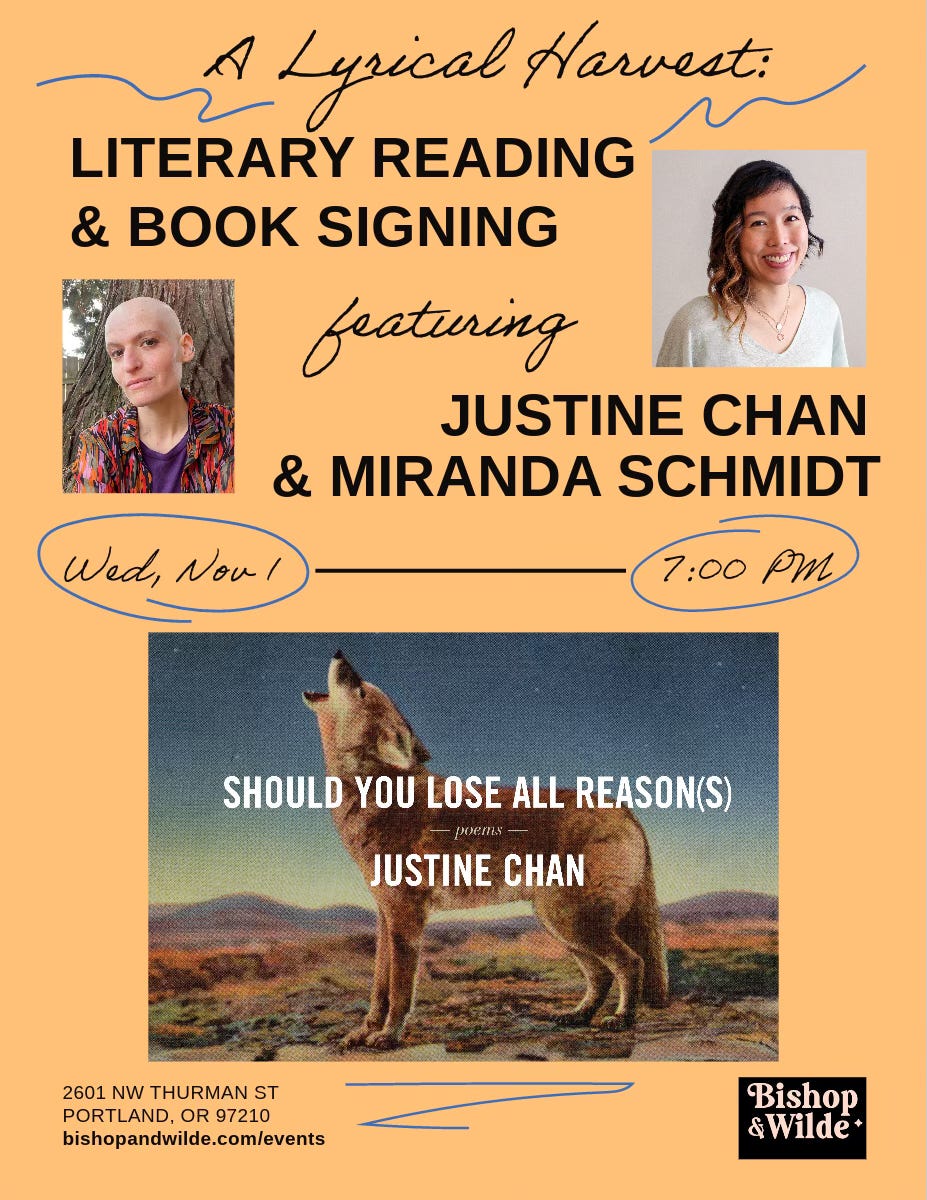

My dear dear friend, the amazing Justine Chan, will be reading from her new book Should You Lose All Reason(s) at Bishop & Wilde on November 1 and I am lucky enough to be reading with her. Justine’s readings are always magical, so if you’re in Portland, you will not want to miss this.

Until next time,

~ Miranda