Earlier this spring, my wife pruned our roses. It looked almost like an act of violence: all the big bushy leafing cut back so mercilessly. But, of course, it’s good for the roses. Later in the spring, they leafed out again. Now, in the summer, they’re still blooming beautifully and, seemingly, quite contentedly.

I can’t bear to prune plants. I always just want to let them be, allow them the space to grow how they will, all wild and gnarled and uneven. I am told this is not good for the plants. This is why I am not a gardener. I can’t ever convince myself that I know better how a plant should grow than the plant themself. And I don’t have the sixth sense for what a plant needs the way my wife does, an intuitive knowing of how to help a being become their fullest most blossoming self.

But I can prune my writing.

I like to think of revision as an act of pruning and growing, winnowing and expansion, taking something away so something else can grow until the writing has found its shape. When I cut away the less lively bits of my work—the extraneous words, the tangled up images, the muddled plot lines, the overly dense sentences—I make space for newness to emerge.

Poetic Distillation

Carrie Etter describes poetry as containing “distillation (focus, concentration, etc.) and musicality. It is through the intensity that comes with focus and musicality (that may come from meter, repetitions of sound, speech rhythms, etc.) that we recognize poetry.”

I love this definition of poetry for how expansive, yet specific, it feels. And I think we often grant poems the permission of intense focus and aesthetic preoccupation in ways that we don’t for prose. We are not surprised when a poem’s confines are narrow, when it takes us through a single moment or image or feeling, expanding the boundaries of that small space until we can experience the fullness of it.

But I find this notion of distillation plus musicality applies to most writing that I most admire, regardless of genre and form. My favorite novels all create a sense of distillation, all have their own musicalities. My favorite short stories often hinge on some combination of intense focus and aesthetic. These are also the elements I find myself most frequently considering when I write in any form: how do I distill this? how do I get to the core of it? how do I find the essence of something and let it breathe through its own rhythms, sounds, styles?

In the novel I’ve been writing, I spent quite a bit of time considering what was absolutely essential to it. I wanted to write a novel that brought the nonhuman further to the forefront of the work. One way I found to do this was to prune back the human story to its most essential and alive feeling parts. I cut everything from secondary human characters to human-centered place names. What grew out of that was a prioritization of nonhuman characters and a more-than-human sense of place that centered ecology and geography over human created boundaries and signifiers. By pruning away the parts of the work that felt less energized and by granting the novel some of the permissions I would grant a poem, I allowed the novel to grow in less expected ways and, in the end, to become more essentially itself.

A Spell for Pruning

Take a piece of writing that you want to revise. Maybe it feels a little unfocused or muddled or like it has too much or too little of something. You probably know the feeling when a piece of writing just has too much extraneous somethings weighing it down or tangling it up. For this exercise, you’ll want a piece of writing that feels like that.

First, go through and highlight the parts of the piece that feel the most energized. Try to focus on the lines, ideas, words that provide the driving force for the work. What is the most essential? What feels the most intriguing to you?

Now, go through with another color and highlight the parts that feel the opposite. What parts of the work feel extraneous, unenergized, dead? What would happen if you pruned these pieces out?

And finally, once you’ve identified the places that feel most essential and the places that feel extraneous, go through and rewrite. If you cut the extraneous away, what does the work become? Is there new writing that grows out of the parts you’ve removed? Does the writing connect differently with the dead bits cut back? Experiment freely. Save your drafts. The great part about writing, as opposed to gardening, is that you can always put things back in if you prune away too much.

A Note

I’ve recently been in the midst of the act of pruning in life as well as in art. Unexpected events have me pairing down to the essentials this summer. And, as I do this, identifying the most alive feeling parts of my life, and focusing there, I find those aspects thriving in surprising new ways. Some of the things that I have chosen to keep are not at all practical or necessarily obviously essential (this humble little newsletter, for instance). But they have an energy in them that feels generative and alive and important. In times of stress or crisis, we’re often told to cut out everything that isn’t absolutely necessary. Often, when discussing revision in writing, we’re told to “kill your darlings,” to pare everything down to the bone and to be absolutely merciless about it. That isn’t the kind of pruning I’m advocating for here. When we take too much away, when we cut away the things we love or enjoy or feel inspired by—even if we don’t fully understand why we love them or, in the moment, what function they serve—we risk pruning away the underlying spirit of the work. So prune with care. Listen as well as you can to the work itself and your own sense of it rather than all the outside critical voices that crowd most of our poor writer brains. Tend to the parts of the work that feel most alive to you and let them grow in their own wild and unexpected ways.

Roots

“The Sense of Distillation: On Prose Poetry” by Carrie Etter in The Craft: A Guide to Making Poetry Happen in the 21st Century edited by Rishi Dastdar

Happenings

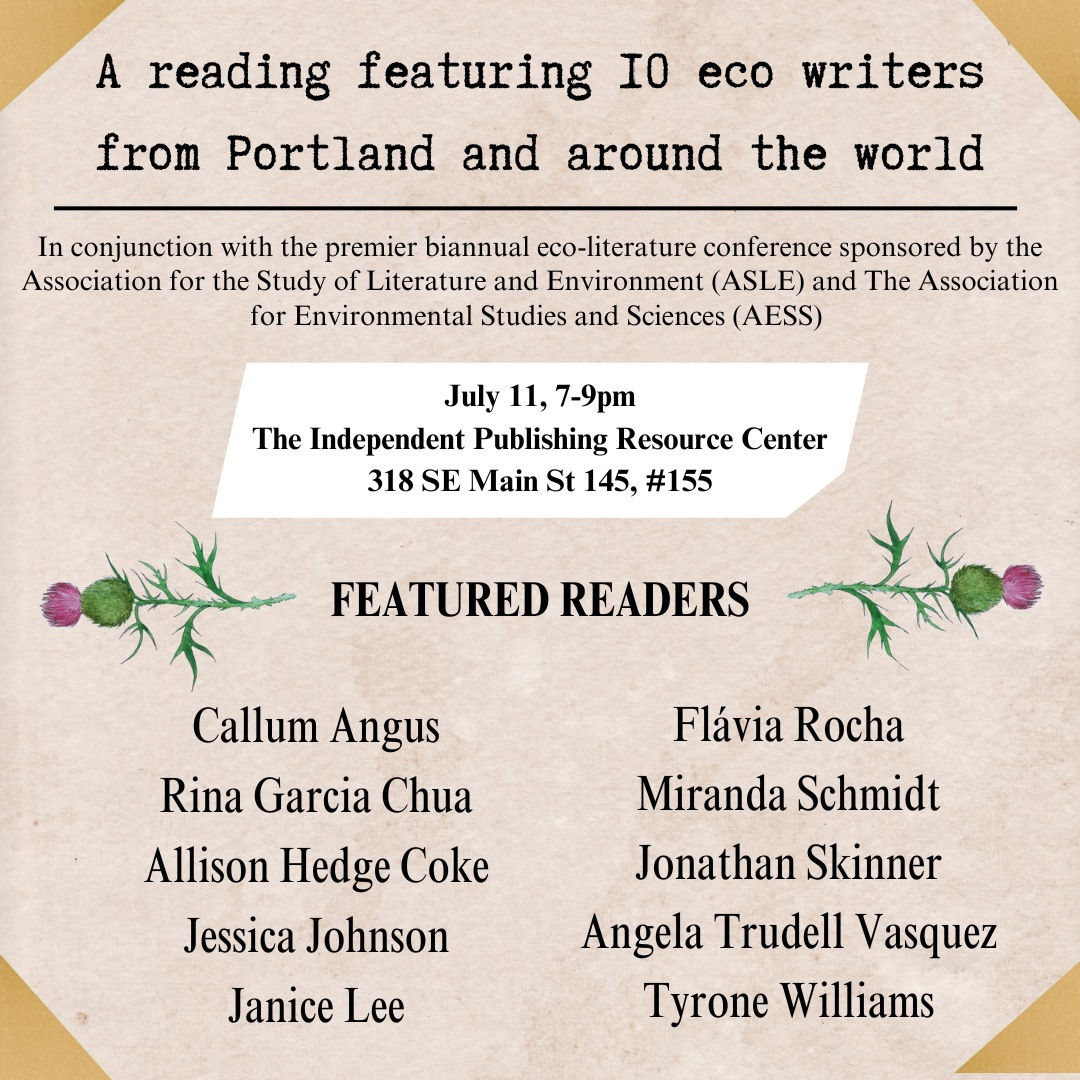

If you’re planning to be in Portland for the ASLE conference in July, I’ll be on a panel called Tales of the Commons, speaking about some of the things I write about in this newsletter. Whether or not you make it out at 8:30 in the morning on a Tuesday to talk craft, if you’re in Portland, please say hi! That evening I’ll also be reading with some incredible eco writers, including my dear talented friend Callum Angus, at the IPRC. This promises to be a really fascinating and dynamic reading, so come if you can!

Until the moon is full again,

~Miranda