The Narrative Depths

Samhain is upon us. Scorpio season is underway. And it’s that deepening time of the year.

Fall is my favorite. Leaves turning. Colors deepening. Light slanting. Keats’ “season of mists and mellow fruitfulness.” Autumn is an uncanny time. Here in Portland, the crows seem at home in it. The rain feels in its element. The moss glows and my mind comes alive. It’s a season of liminal spaces. Samhain, Halloween, Día de los Muertos – these are all days to mark the dead. Days when the veil between states is said to thin. Times when we can delve into the dark of heritage and legacy, of our inner and our outer worlds. Fall is a season to move toward the depths. It’s also the season I was born into.

When I tell people my sun sign, I like to say, “I’m a Scorpio. I’m not afraid of the dark.” I’ve seen Scorpio described as the deep well of the water signs of the zodiac. There’s an intensity to this sign that I identify with, a curiosity that can look obsessive, a commitment to deepening that can look relentless. This is one of the core spaces I write from. For me, writing a novel can feel like a journey to the underworld and back. It’s never fully logical. It often doesn’t make sense. It can be frightening and beautiful and dreamlike and strange. Each time, I come back changed and holding something I didn’t expect.

Reshaping Stories

In my last newsletter, I wrote about narrative structures and how the arcing narrative structure so many of us are taught to write in doesn’t always fit what we want to write. Ursula K. Le Guin wrote about this in her essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” I remember finding this essay for the first time in college and feeling a whole world open up to me. Le Guin argued that our predominate western narrative structures (often spoken of as “the hero’s journey” or often represented by the Freytag Pyramid) are only suited to describing a very narrow set of lived experiences and that these structures can lend themselves to very individualistic and antagonistic modes of thinking. A structure like this moves toward a climax in which something or someone must be defeated or overcome. The narrative tension arises from conflict.

What if, Le Guin proposed, we thought of our stories in another structure, not so much as an arcing arrow, but as a bag that held many things? What if the narrative tension arose from the relationship between those things rather than from conflict?

“A book holds words. Words hold things. They bear meanings. A novel is a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us.”

- Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”

I’ve always loved this way of thinking of stories and the telling of them. It feels so full of possibility to me. I find it particularly useful to think of narrative tension as something other than conflict. Conflict isn’t the only dynamic force that can drive a story. Movement, growth, friction, derives from so much more.

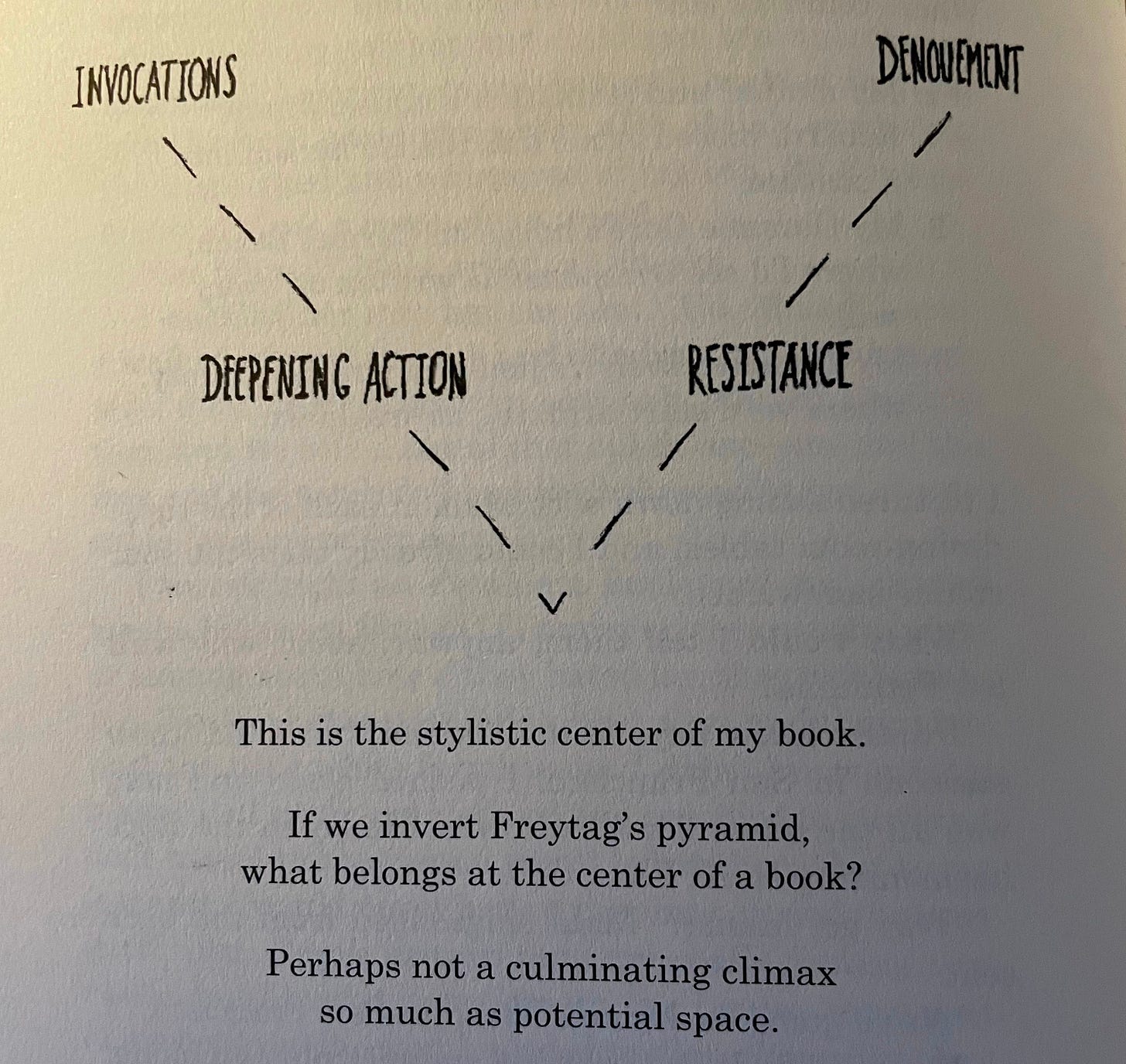

What if we build our narratives not toward a climax, but toward a deepening? This is what Ariel Gore asks in We Were Witches, suggesting an alternative narrative structure that moves toward “potential space” rather than “a culminating climax.” And this is precisely what she does, placing an inverted pyramid at the very center of her book:

Ariel Gore’s deepening action is one of discovery. Hers is a book of learning—about the world, about one’s own power, about the ability to shape one’s own story. Her deepening comes with a sense of expansion.

Another recent novel I see as a deepening, but one that narrows rather than expands, is Julia Armfield’s Our Wives Under the Sea. This story follows two tales of a marriage: Leah’s record of her mysterious submarine mission that brought her back to her wife changed, and Miri’s account of Leah’s slow dissolution into a sea creature upon her return. It’s an intense story of love and grief. Structurally, these two accounts seem to spiral around each other, plumbing the depths of love and self. The momentum of the story is heightened by its sense of containment— physically, Leah’s part of the tale takes place on a submarine and Miri’s takes place mostly in their apartment. The novel is, to my mind, willfully uneventful and quiet. And I love this about it. Again and again it defied my expectations of a book about a fantastical transformation and, in defying these expectations, in the ways that it focused and narrowed in its deepening, it plunged me into the emotional realities of loss.

A Spell for Finding Shape

Imagine the narrative structure of your project is a shape—what shape would it be? Try to draw it. Chart it. Is it a pyramid, an inverted triangle, a bag, a spiral, a wave, a line, a seed, the arc of a bird taking flight, a mushroom, a root system, a tree? It can be any shape you want. It doesn’t have to fit exactly. Think about the movements of your piece, the tensions and relationships of it. Consider what drives it. The point of this exercise isn’t precision so much as thinking of all the different ways we can conceptualize a narrative. It’s about opening up possibilities.

Roots

Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”

Julia Armfield, Our Wives Under the Sea

Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative by Jane Alison

Happenings

My forthcoming novel, Leafskin, is officially available for preorders. Preorders are a really wonderful way to show support for a forthcoming book, particularly a small press title like this one, so please check it out if you’d like to! Leafskin’s publication date is March 25, 2025 so if you preorder a book now, it will be sent to you this spring. The publisher is currently working on the cover, which I’m hoping to reveal next month when I write about my experience of some of the many different arts that go into a novel.

Thanks for reading!

Until the next one,

Miranda